"The Sociological Imagination" is a brilliant meditation on the meaning and importance of sociology by C. Wright Mills. Contains some important points about methods in social research and the history of sociology as an academic discipline. But the highlight of the book is the chapter in which Mills rips to shreds the bombastic rhetoric of Talcott Parsons.

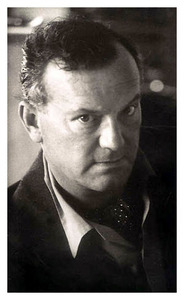

Charles Wright Mills (1916-1962) was one of the most influential radical social theorists and critics in twentieth century America. His work continues to have considerable significance. Here we focus on his connecting of private troubles and public issues; his exploration of power relationships; and his approach to 'doing' sociology.

contents: introduction · life · power · public issues and private troubles · on intellectual craftsmanship · conclusion · further reading and references · how to cite this piece

contents: introduction · life · power · public issues and private troubles · on intellectual craftsmanship · conclusion · further reading and references · how to cite this piece

C . Wright Mills was a controversial and larger than life figure. He was a vociferous reader, a superb writer - and was able to make a distinctive contribution to American sociological theory especially in the area of class, power and social structure. He was anti-authoritarian, flamboyant and individualistic. John Elridge (1983: 112) has concluded that C. Wright Mills made a significant contribution in three areas.

First, 'his fusion of American pragmatism and European sociology did lead to innovative work in the sociology of knowledge'.

Second, he completed a substantial range of studies in what was a short working life. Each had its strengths and weaknesses but together they reflect a concern to 'understand American society and its place in world affairs'.

Last, he provided a considerable and lasting intellectual stimulus to others. We can see his mark in Tom Bottomore's (1966) exploration of elites and Steven Lukes (1973) seminal discussion of power, for example - and in the work of Alvin Gouldner.

For informal educators and those working in the social professions, his critique of the professional ideology of social pathology remains highly pertinent. But perhaps the best way of remembering his contribution is the advice he gives in the closing paragraphs of the The Sociological Imagination:

Do not allow public issues as they are officially formulated, or troubles as they are privately felt, to determine the problems that you take up for study. Above all, do not give up your moral and political autonomy by accepting in somebody else's terms the illiberal practicality of the bureaucratic ethos or the liberal practicality of the moral scatter. Know that many personal troubles cannot be solved merely as troubles, but must be understood in terms of public issues - and in terms of the problems of history making. Know that the human meaning of public issues must be revealed by relating them to personal troubles - and to the problems of the individual life. Know that the problems of social science, when adequately formulated, must include both troubles and issues, both biography and history, and the range of their intricate relations. Within that range the life of the individual and the making of societies occur; and within that range the sociological imagination has its chance to make a difference in the quality of human life in our time. (Mills 1959: 226)

First, 'his fusion of American pragmatism and European sociology did lead to innovative work in the sociology of knowledge'.

Second, he completed a substantial range of studies in what was a short working life. Each had its strengths and weaknesses but together they reflect a concern to 'understand American society and its place in world affairs'.

Last, he provided a considerable and lasting intellectual stimulus to others. We can see his mark in Tom Bottomore's (1966) exploration of elites and Steven Lukes (1973) seminal discussion of power, for example - and in the work of Alvin Gouldner.

For informal educators and those working in the social professions, his critique of the professional ideology of social pathology remains highly pertinent. But perhaps the best way of remembering his contribution is the advice he gives in the closing paragraphs of the The Sociological Imagination:

Do not allow public issues as they are officially formulated, or troubles as they are privately felt, to determine the problems that you take up for study. Above all, do not give up your moral and political autonomy by accepting in somebody else's terms the illiberal practicality of the bureaucratic ethos or the liberal practicality of the moral scatter. Know that many personal troubles cannot be solved merely as troubles, but must be understood in terms of public issues - and in terms of the problems of history making. Know that the human meaning of public issues must be revealed by relating them to personal troubles - and to the problems of the individual life. Know that the problems of social science, when adequately formulated, must include both troubles and issues, both biography and history, and the range of their intricate relations. Within that range the life of the individual and the making of societies occur; and within that range the sociological imagination has its chance to make a difference in the quality of human life in our time. (Mills 1959: 226)